This post was migrated from my old blog which used to be hosted on Blogger. As a result, some links might be broken.

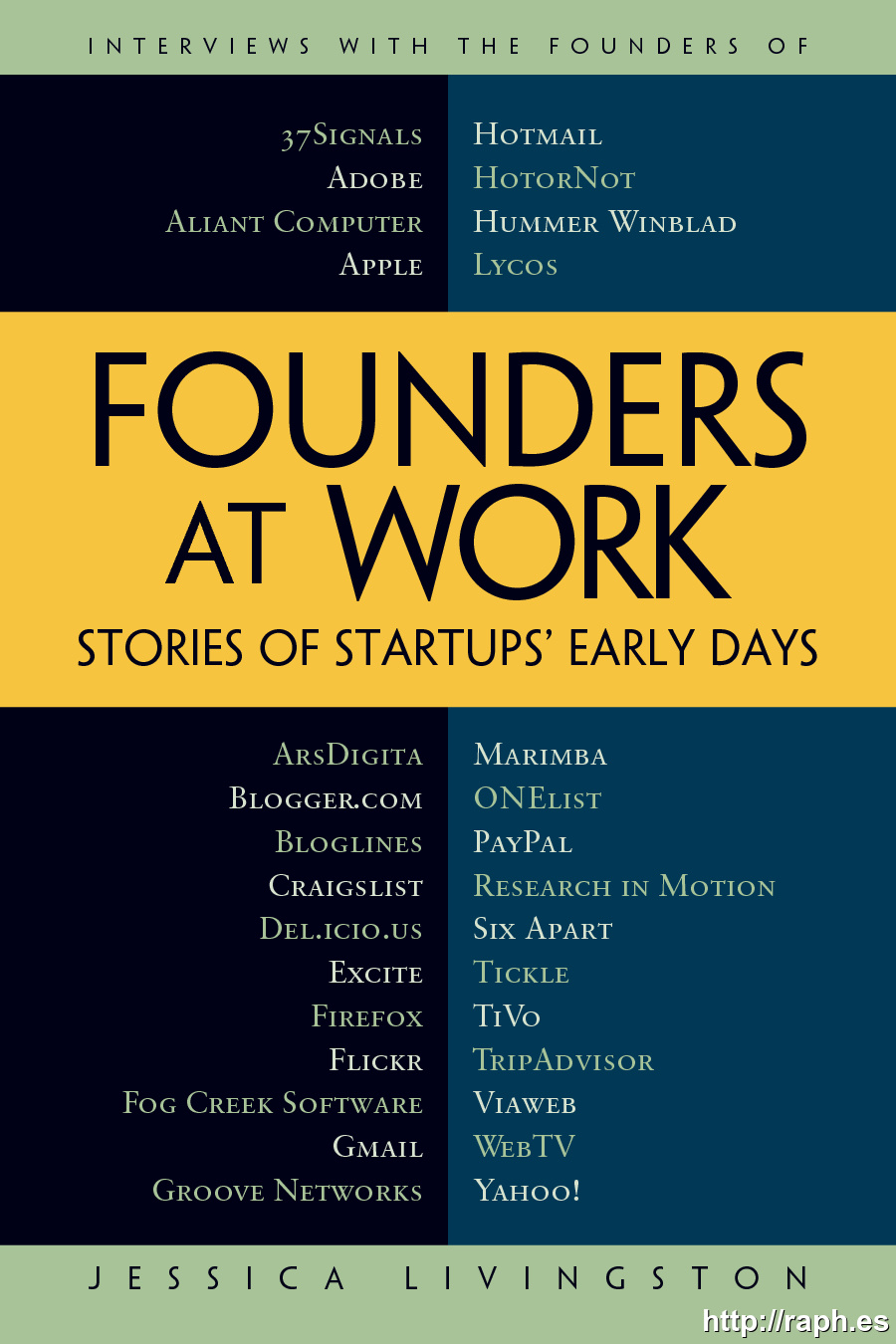

A few weeks ago, I finished reading the book Founders at Work by Jessica Livingston. It’s a collection of interviews with founders and early employees of various (successful!) technology companies. Many of them are web start-ups founded in the era of the dot-com bubble. They talk about how they got started, highs and lows, good and bad experiences with venture capitalists and lots of funny things that happened along the way.

I have to admit it was the big names on the cover that caught my attention initially. It then surprised me that those were actually the worst parts of the book. While the big players’ stories do have some interesting bits and pieces, they come across too polished. Kind of how you might expect successful entrepeneurs to sound when they brag about their success. So, to my own surpsise, I found myself rushing through the stories about Yahoo, Firefox, Lycos, Lotus, Hotmail, PayPal, Craigslist and Gmail, eager for them to finish. Exceptions: Flickr, RIM, TiVo and Apple.

The interviews with the less known founders, on the other hand, feel more authentic and personal. When I say “less known”, I mean I had no idea who they were before reading this book. Although in fact I was familiar with some of their products (e.g. Six Apart’s TypePad). The way they tell their stories, particularly how they reflect on the personal side, makes these so much more interesting. They are the ones that kept me from putting the book down, and they totally make up for some of the more tiring chapters. Great interviews that come to my mind (in no particular order) would be those with ArsDigita, Blogger, Hot or Not, Six Apart, Viaweb and Shareholder.com.

Some of my favorites also happen to be with people who are somehow affiliated with the author and her own company Y Combinator, sort of a micro-investor that aims to support other startups. My guess is that they were able to focus their stories to be closer to the core message of the book, which is very much in line with the mission of Y Combinator. Another possibility is that the “older” generation of industry veterans simply does not like to share very personal information as much as the younger blogging generation does. But I’m just speculating here.

Interestingly, Gmail is the closest the book gets to Google. Somehow I instinctively associate the ad search meh giant with the term “startup” (kudos to their CI team, I guess) so I expected them to be featured. Maybe their story is just too popular? But on the other hand, Apple is in it, and their history must be one of the best-known out there considering the legions of fan-boys that are in love with Steve Jobs. That and it’s coverage in other books. Nevertheless, Steve Wozniak (the other Steve) gives what I felt was the longest and most self-praising interview in the entire book.

Excited about the newest iThing?

This is of course just my opinion, and I am sure that you’d pull out other things from this book. Either way, it is a pure goldmine for good quotes. I will present and comment on some of my personal favorites below (again, in no particular order). There’s so many more I’d love to put up here, but this is already more than I can probably expect anyone out there to read. It should be quite obvious at this point that I enjoyed reading this book, most parts of it anyway. It’s full of good advice for those of you who are planning on starting a company (albeit somewhat Silicon Valley specific) and for anyone else who is just interested in getting some fresh perspectives on the past and present world of IT start-ups.

My coworkers at Morgan [Stanley] were smart people. One of the people we worked with won the Nobel Prize for economics while I was there. It was a fast, smart environment. I remember when I interviewed at Google the first time around and they were making derogatory comments about where I worked: “Well, here you’ll get to work with PhDs and computer scientists.” And I’m like, “I already do.”

I like this because it is so true. Financial trading has a very high concentration of extremely smart people and yet apparently many people don’t believe that. It’s an industry with very interesting technical challenges and (obviously) tons of resources, making it an attractive career choice. Some of the brightest people I have ever met work in the financial software industry.

(…) programmers are very unlikeable people. They’re not pleasant to manage. In aviation, for example, people who greatly overestimate their level of skill are all dead. You don’t see them as employess. J.F.K., Jr., is not working at a Part 135 charter operation because he’s dead. It’s not that he was a bad pilot; it’s just that his level of confidence to level of skill ratio was out of whack, and he made a bunch of bad decisions that led to him dying, which is unfortunate. In aviation, by the time someone might be your employee, probably their perceived skill and their actual skill are reasonably in line. In IT, you have people who think, “I’m a really great driver, I’m a great lover, I’m a great programmer.” But where are the metrics that are going to prove them wrong? Traffic accidents are very infrequent, so they don’t get the feedback that they are a terrible driver because it’s so unlikely that the’ll get into an accident. A girlfriend leaves them - well, it was certainly her deep-seated psychological problems from childhood. Their code fails to ship to customers. It was marketing’s fault!”

This is probably my favorite part of the book. It points out something that I believe is a serious problem in most software development teams. Many engineers massively overestimate their own capabilities, especially so-called “senior” people. They are convinced that what they do is perfect and won’t consider that they might be able to improve their skills. “I don’t need unit tests because I write working code”. Sure… That makes evolving a team unnecessarily difficult (albeit, thank goodness, not impossible!).

In aviation, Darwin takes care of Mavericks.

img: Wikipedia

I think the main thing [why users liked Viaweb] is that it was easy. Practically all the software in the world is either broken or very difficult to use. So users dread software. They’ve been trained that whenever they try to install something, or even fill out a form online, it’s not going to work. I dread installing stuff, and I have a PhD in computer science.

Not much to add here. It reminds me of Apple’s highly user-centric design philosophy - and how successful it is, particularly with less tech-savvy customers. As obvious as it may seem, it takes dedication and discipline to go through with it.

If I’m forced to think about women who are in this field, I can’t usually. But I know there are. Many women are in marketing or design. I think marketing and design are a lot harder to learn than engineering. That’s my opinion. People put value judgements on engineering like, “There are more men; therefore, it must be a smarter field that women should get into.” (…) There aren’t that many women in technology and maybe it doesn’t really matter. I mean, why aren’t there more men in design?

I believe Ms. Trott makes a good point here. So the number of women in IT is not as high as some arbitrary percentage people decided would be “fair” - who cares? Maybe it’s just something most women don’t like to do, and that’s that? Back when I was at the University my programme was a mix of computer science and design. The male/female ratio was fairly balanced. Until we had to decide what to specialize on: CS or the design thing. Nearly all the women went for design, leaving mostly guys in the CS classes. It was a natural decision, those ladies simply wanted to do design. While preconceptions based on stereotypes can be harmful and encouraging them is not good, we should not try to force them out of existence, either. For example, most boys like trucks while girls usually prefer dolls. Not wanting girls to play with trucks would be just as harmful as not wanting them to play with dolls, just for the sake of eradicating a stereotype. To get back to the point: maybe most women simply prefer design over software development. Don’t try to draw more women into the field just in order to make a point. Having said that, I do think that more female software developers could really benefit the industry.

Flags mark the many quotes I enjoyed.

(…) when you are hardware designers, you have tremendously more discipline in writing and describing software because in hardware you cannot get it wrong. Every turn of every chip costs you millions of dollars, so when hardware designers design any piece of software, they normally get it right. They use something called state machines to describe the functioning of the software. (…) So you write it in a very deterministic fashion and therefore you tend not to make too many mistakes. Whereas the pure software writers - the way they think and architect software is very creative. (…) So in terms of being able to test it out, there is somewhat of a difference, but I just think that hardware designers would be pretty good software designers as well.

He interchangeably uses the terms “software writers”, “architect” and software designers” here, so I might be misunderstanding him a bit. But to me it reads like he is saying that hardware hackers could easily be good software developers if they only wanted to, whereas the other way around it would not work. I have to disagree. One thing that distinguishes software from most other domains is that a software project is subject to constant change. That’s why comparing it with construction, or in this case, hardware, just does not work well. Hardware hackers might make good programmers. But there is a big difference between programming and software development. Programming is a skill you need in order to develop software, but there is much more to it. Because it’s about developing software: that means not just getting it right at one point in time, but evolving it over a period of time. A whole set of other skills are required for that than just knowing how to draw a state machine.

So we got a really good first round of funding - $4 million from Kleiner Perkins. Though I thought they wired the money in these situations, they actually gave us a check. So we had two checks (…) and Sami goes, “Let’s go to Kinko’s and make copies!” So he takes the checks to Kinko’s and comes back with the photocopies, and he forgot to take the checks out of the copy machine! Luckily they were still there. All the early people that had been there 3 to 4 years were starting to leave. Morale was very low, and so I went to the CFO and said, “Look, I want to buy an espresso machine.” And he said, “No, we can’t do that, it’s too expensive.” A few weeks later, when another senior engineer quit, I said, “Screw it, let’s go buy an espresso machine.” So Jonathan and I went online and bought this super-duper Italian, fully automatic, $15,000 espresso machine on his credit card and submitted the expense form. The CFO almost had a baby. It was unbelievable. (…) and it was the best money we ever spent. Every morning, people would meet and crowd around it. This thing was just it, the bee’s knees, people loved it, they couldn’t stop talking about it. A month later, the CFO came and said, “I’m sorry, we should have done this years ago.”

He continues to explain that you should be willing to invest into creating a working environment that people enjoy working in. Losing them to competition is much more expensive in the long run. And it’s the long-term things that some people tend to lose out of sight.

If you were an alien and you came here in 1991 and you wanted to learn how to develop software, you would learn ten times as much at Microsoft as anywhere else, I think (…) Now Microsoft has forgotten all these things, and they’ve hired a lot of morons that don’t know these things anymore. I think that now Microsoft is kind of a big tar pit where you can barely move forward because there’s so much bueaucracy. But I learned a lot.

It’s interesting to see how innovation remains largely concentrated within start-ups, no matter how hard bigger, more established companies try to preserve that culture. Google, your typical hip start-up from yesteryear, now appears to be at the point where Microsoft was in the early nineties. The circle of life, I suppose.

So the article came out and the server got slammed. (…) we took the site down, grabbed an extra PC (…) and drove to Berkeley where Jim had a shared office. I remember taking the top off a case for pushpins and mounting it on top of the power switch of the machine so no one could turn it off. Then we put it in the corner under his desk and surrounded it with books, so it just looked like a bunch of stuff under his desk with a little Ethernet cable coming out.

I guess I like this one because it reminds me of how some friends of mine ran their web design company’s project server from inside the University for over a year. That counts as education, right?

I originally had my parents moderating since they were retired, and after a few days I asked my dad how it was going. He said, “Oh, it’s really interesting. Mom saw a picture of a guy and a girl and another girl and they were doing…” So I told Jim, “Dude, my parents can’t do this any more. They’re looking at porn all day.”

Funny for all the wrong reasons.